An international conference in Italy led to a chance encounter between three unlikely friends: an automotive engineer, an oral biologist, and a food scientist. And the rest, as they say, is history. That is, part of Motif’s innovative food science and technology history, and the foundation for a bold partnership between Motif FoodWorks, King’s College London, and Imperial College London.

In northern Italy, the fifth World Tribology Congress brought together world-class experts obsessed with tribology, the study of how surfaces in relative motion interact with one another. Most of the researchers and industry heavyweights in attendance are not food scientists, but engineers and physicists furthering the field of mechanical lubrication, friction, and wear and tear.

But that didn’t stop Dr. Stefan Baier, now Motif FoodWorks’ Head of Food Science, from flying halfway around the world to listen to what these experts had to say. As a food scientist, he certainly stuck out. Yet at that conference he began sowing the seeds for an interesting partnership with implications for how we measure and perceive food.

In food, tribology comes into play when attempting to manage and mitigate astringency, a dry, puckering mouthfeel that’s often associated with substances like coffee, tea, wine, and some types of unripened fruit. Astringency has been a particular, long-standing challenge for plant-based food product researchers. Plant-based products are meant to mimic their animal-based counterparts in a myriad of ways, but an astringent sensation – often present in plant-based products – is not part of the oral experience of animal-based products.

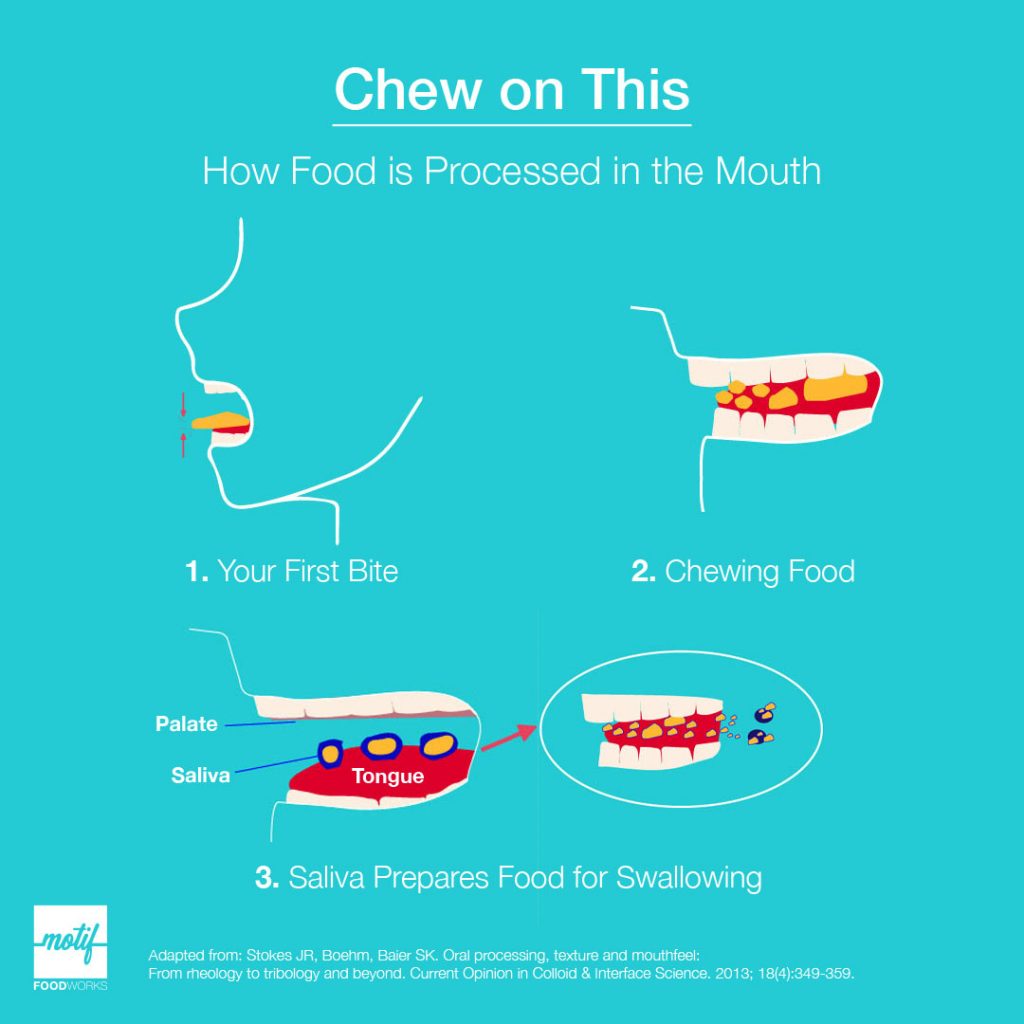

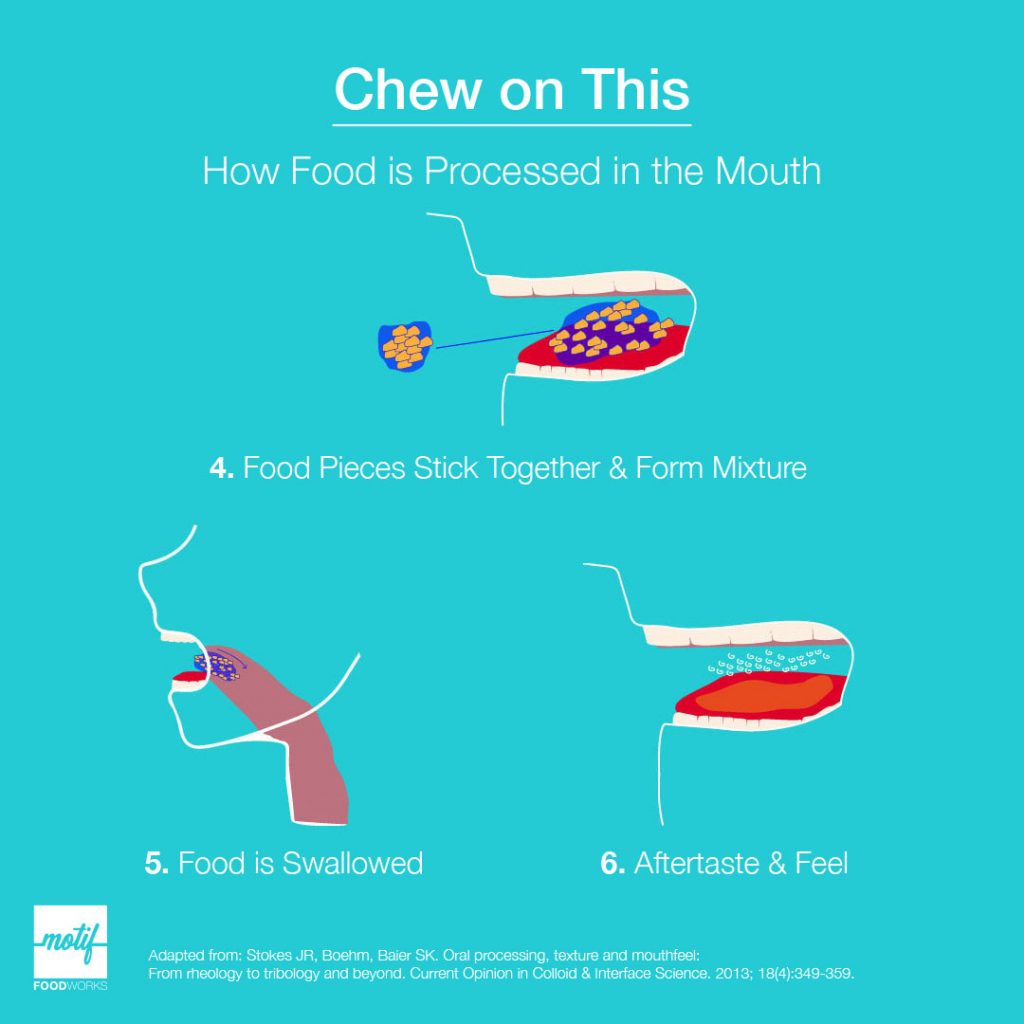

“What puzzles me in the food space is that most of the experience that we are trying to sell happens in your mouth,” said Dr. Baier. “But we don’t know how texture develops throughout the full experience of oral processing. So I became focused on the intricate rheology, the science of flow and deformation, and the tribology of these experiences. They’re key to understanding the rules that create these very specific positive and negative effects in the mouth.”

Dr. Baier’s astringency solution was to find the biggest gathering of international researchers who could show him, chemically and mechanically, how to harness the power of tribology to solve this challenge. Sitting at a bar in Torino after the conference, Dr. Baier struck up a conversation with Dr. Thomas Reddyhoff, a senior lecturer within the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London. Dr. Reddyhoff was surprised to learn Dr. Baier was a conference attendee, and was curious about why a lone food scientist was 4,000 miles away from home just to hear a bunch of mechanical wear and tear experts talk about mostly industrial and automotive solutions.

Naturally, even bar food came into play; “Regarding texture, you don’t say ‘I had a particularly crunchy chip today’ but you can tell when it’s soggy and stale,” said Dr. Baier. The two talked at length about this and other fascinating intersections of their respective fields, and walked away from that conference with a plan to solve plant food science’s most perplexing challenges.

“Our mission in our partnership with Motif has been trying to understand what drives the mouth perception of taste and feel,” said Dr. Reddyhoff. “By exploring the basic science behind what makes eating enjoyable, we’re helping Motif’s customers better formulate their plant-based products to make them more palatable, passing along health benefits and aiding in consumer adoption of more sustainable options.”

One of the food industry’s research blind spots is the impact of saliva lubrication on how we perceive taste and texture, which is also a factor in removing the astringent sensation. To take his collaboration with Imperial’s efforts a step further, Dr. Baier put out a call to his colleagues for an oral biology expert, which led to a three way partnership with Professor Guy Carpenter and his department in the Faculty of Dental, Oral and Craniofacial Sciences at King’s College London.

“So much about the impact of saliva on taste is still unknown, largely because it’s a challenging substance to study in an experimental setting,” said Professor Carpenter. “We realized that to make significant progress in this space we needed to bring people together from different disciplines. This partnership is an exceptional opportunity in that regard, especially because we have the freedom to take an investigative approach.”

Pairing oral biology and dental experts with automotive and mechanical engineers, and a food scientist means that each member group tackles a unique part of the solution: Imperial’s experts focus on the mechanical and lubrication physics of Motif’s ingredients, and the King’s team focuses on the physics of what happens in the mouth during chewing. Between the two, they’ve already developed a new way to measure astringency in the mouth. This has helped Motif’s Food Science team uncover new data-driven insights that are already helping formulate better tasting plant-based food.

The three-way partnership is supported by both a London Interdisciplinary Doctoral program (LIDo) grant and an Imperial SME grant. This effort joins Motif’s growing network of scientific collaborators working together to unleash the promise of plant-based food, and comes on the heels of an exclusive licensing agreement with the University of Guelph and Coasun, Inc. to improve the texture of plant-based meat and cheese alternatives, as well as ongoing research partnerships with University of Illinois, University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of Queensland.